乖的文化是家庭教育的致命傷。乖的文化並不培養孩子思考、分析、判斷、異議和解難的能力。父母是害怕孩子不需要自己,失去他們?還是不願見到孩子長大?抑或害怕孩子不再聽命於自己,挑戰自己?還是害怕自己的自尊心受損?乖的文化是一種依附的文化,並不着意使子女成為獨立的人。事事需諮詢父母,由父母作主!乖的文化不單建立倚賴的意識,更建立免責的意識。

乖的文化的另一端是放任文化。由於現在流行反傳統的管教方式,體罰須負上法律責任,又強調親子關係,在打駡中長大的父母往往無所適從,於是事事由子女決定,由子女的喜好作主,聽命於子女,卻沒有教導子女行事為人的原則,處人處事的價值。子女成為家庭轉動的軸心,父母為子女鞠躬盡瘁、死而後已。於是制造了一批難以合作的小霸王。嚴厲和放任,往往弔詭地在同一家庭出現!

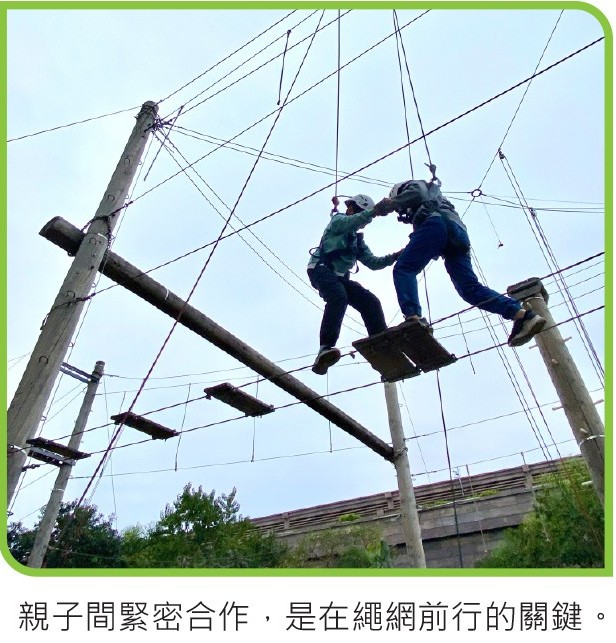

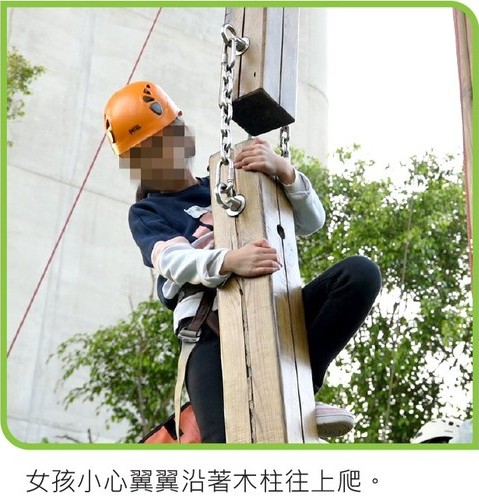

過去父母的父母為口奔馳,子女眾多,無暇照顧子女。於是這一代的父母彷彿彌補他們所缺乏的父愛和母愛,加上現在生活環境改善,子女少,容易對子女過分保護和關懷,事事為子女安排和出頭,唯恐子女出錯、失敗、失望或不快,於是不鼓勵冒險,窒礙子女獨立成長,也剝奪子女嘗試、掙扎或犯錯的機會。過分保護和乖的文化往往同枝連氣,令孩子日後產生不少處人處事的困難。子女出來社會工作,很容易逃避和崩潰,因為無法應付複雜的人事問題。

家庭的價值教育

父母與子女的相處,處處顯出父母的價值觀,也不經意把這些價值觀傳給子女。例如跑進地鐵「霸位」,傳達了做人不可「執輸」,切勿吃虧,每個人都是競爭對手,必須「跑贏」其他人,勝過別人,做人必須尋求自我利益最大化的心態。坐地鐵讓位,傳達了尊重和關懷,體恤有需要的人,對人的需要敏銳,互助互愛等價值。

從第二節提出的基督教人觀,可對價值教育作以下的引伸。就人的被造性而言,人是按上帝的形象所造,因此具尊嚴,是目的本身(End-in-itself)而非達至目的的途徑(Means-to-an-end);是故人有不可褫奪的一面,亦即基本人權所提到的。上帝賦予人意義、目的、召命,去完成上帝的托付,活出生命的意義。再者,每個人在上帝眼中人是特殊的、獨一無二的、不可替代的,也是上帝所珍惜和愛護的。意即人是寳貴的。

從人是身心理序的合一體,可推出人的身體是尊貴的,是構成人之為人的基要組件,需要尊重、保養和照顧,建立良好的生活習慣和健康的起居飲食文化,抗衡對身體具傷害性的活動或惡習,例如吸毒。人具物質性,與環境結連,故須培養環境保護的意識。同理,人的心靈是寳貴的,需要多多珍惜和維護,聆聽和正視內心的需要和感受,關注心理健康。身體與心靈的合一,在性方面尤其突顯。身體與心靈衝突的性行動,會對人造成無法彌補的傷害,例如援交。

[1]參Karl Barth, “Man as the Creature of God,” section 44 in

Church Dogmatics III/2 (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1960), 55–202; Paul K. Jewett with Marguerite Shuster,

Who We Are: Our dignity as Human, A Neo-Evangelical Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 179–183; Ray S. Anderson, “Humanity as Determined by the Word of God,” chap. in

On Being Human: Essays in Theological Anthropology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 33–43; Michael Welker, Is the Autonomous Person of European Modernity a sustainable Model of Human Personhood?” in

The Human Person in Science and Theology, ed. by Niels Henrik Gregersen, Willem B. Drees, and Ulf Görman (Edinburgh:n T & T clark, 2000), 95–114; J. van Genderen and W. H. Velema,

Concise Reformed Dogmatics, tr. by Gerrit Bilkes and Ed M. van der Maas (Phillipsburg: P&R, 2008), 357–368: ; Philip A. Rolnick, “The Human Person,” chap. in

Person, Grace, and God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 208–256.

[2]參Barth, “Man in Soul and Body,” section 46 in

Church Dogmatics III/2, 325–436; Jewett with Shuster,

Who We Are, 26–44; Anderson, “Humanity as Creatureliness,” chap. in

On Being Human, 20–32; D. Gareth Jones, “The Emergence of Persons,” in from Cells to Souls – and Beyond, ed. by Malcolm Jeeves (Grand Rapids: Eeerdmans, 2004), 11–33; John Cooper.

Body, Sol, and Life Everlasting: Biblical Anthropology and the Monism-Dualism Debate (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989); van Genderen and Velema,

Concise Reformed Dogmatics, 346–357; Gordon J. Spykman,

Reformational Theology: A New Paradigm for Doing Dogmatics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 233–245.

[3]參Martin Buber,

I and Thou. A new translation with a Prologue “I and You” and Notes by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1970); John Macmurray, “The Perception of the Other,” chap. In

The Self as Agent (London: Faber and Faber, 1957), 104–126; Emmanuel Levinas,

Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969) ; Anderson, “Humanity as Determined by the Other,” chap. in

On Being Human, 44–54; John D Zizioulas, “Personhood and Being,” chap. in

Being as Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church (Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1985), 27–65; John Macmurray, “The Field of the Personal,” “Mother and Child,” “The Discrimination of the Other,” “The Rhythm of Withdrawal and Return,”

Persons in Relation (New Jersey and London: Humanities Press International, 1961), 15–43, 44–63, 64–85, 86–105; Rolnick, “Gift: Summoned, Interrogated, Enjoyed,” chap. in

Person, Grace, and God, 144–185; Barth, “Man in His Determination as the Covenant-Partner of God,” section 45 in

Church Dogmatics III/2, 203–324.

[4]參Jewett with Shuster,

Who We Are, 59–84; Macmurray, “Agent and Subject,” and “Implications of Action,” chaps. In

The Self as Agent, 84–103,127–145; Anderson, “Humanity as Self-Determined,” chap. in

On Being Human, 55–65; John F. Crosby,

The Selfhood of the Human Person (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1996).

[5]參Jewett with Shuster,

Who We Are, 351–465; van Genderen and Velema,

Concise Reformed Dogmatics, 368–374; Spykman,

Reformational Theology, 245–249.

[6]參Anderson, “Being Human – in Contradiction and in Hope,” chap. in

On Being Human, 88–103; van Genderen and Velema, “Sin,” chap. in

Concise Reformed Dogmatics, 385–436; Ted Peters,

Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994): Cornelius Plantinga, Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: A Braviary of Sin (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995); Karl Menninger,

Whatever Became of Sin? (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1975).

[7]參Josh McDowell,

How to be a Hero to Your Kids (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1993).